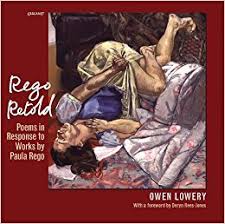

Rego Retold Poems in Response to Works by Paula Rego

Indisputably, Emily Dickinson’s “Tell it Slant” works, but does her entreatment apply solely to poets?

Indisputably, Emily Dickinson’s “Tell it Slant” works, but does her entreatment apply solely to poets?

In Rego Retold Owen Lowery has rightly termed his collection “Poems in Response” (my italics). Ekphrastic poetry has many detractors; done badly there is reason for critical disquiet. If we are all in some way telling it slant then any attempt to explain or define in another medium risks a dumbing down, or re-telling what’s already told. And Why would you?

In this handsome volume, Paula Rego’s work is arranged chronologically (1986-2013). Each Lowery poem faces a painting and shares its title, seeking to unpick the venerable Portuguese artist’s images. Elsewhere, Lowery has described his “obsession” with Rego’s output, and her long career merits such scrutiny. She has been disparaging of those overstating her work’s sexual element, but certainly there are disquieting, sexually-ominous questions and she does deliver a strong feminist punch. Perhaps ekphrasis is more arduous when the artist is alive, but Rego appears content.

Should we try to think more of how ekphrasis can work? Deryn Rees-Jones’ foreword is a succinct and wise exploration of its tensions. Her well-made point about Lowery’s consistent use of third person here shows how he circumnavigates “the risk of overwriting transgressive female art with a male voice”. These are poems which understand both risk and respect, and do not offer any “explanation”, nor God forbid, do they mansplain.

Rego’s paintings sometimes bring me Steven Campbell’s narrative quirkiness, others recall Kahlo and some later works offer Daumier. Her own openly-expressed “after” references Hogarth. I enjoy the strong resonances of her fellow-Iberian Goya, particularly of his “Los caprichos”. One of the great wonders of those aquatints and etchings is that they were and remain an unresolved narrative. Nightmares of political turbulence? Goya’s own fragile mental health? There we have the pact between art and viewer.

Now, consider Lowery’s response to “Departure”:

his face has time to

react, his default will be

that expression birds

are shot wearing. The photos

can be kept on tenterhooks[.]

In responding to that painting and title, some might have recognised the looming wall of Ericeira’s Praia dos Pescadores (Rego was long resident in the town) and tied lines to the expulsion of Portugal’s last monarch which took place there in 1910. In responding to Art, we all carry baggage. I unloaded some of my own in the paragraph above. However, that luggage is not the artist’s. She has her own. Possibly the real danger in ekphrasis is if it claims to define our predecessor artist’s intent. Let’s leave telling it straight to legal and medical situations; the creative telling is slant.

When unravelling ekphrasis, we should look at Rego’s own sources. Consider her keen interest in folklore, particularly seen through the filter of children’s picture books. Now, we can also move down the chain. Sometimes (for my tastes) Lowery’s rhymes seem rather frequent and full, his stanzaic structure slightly predictable and his fondness for cliff-edge enjambment a tad overdone… but then Lowery is a performance poet, and the page is unlikely to be his terminus. There has been much recent poetry discussion on page versus stage– discussion which at best has been interesting, but at worst polarised and personalised on both sides. Alas, the argument stared horrified at a fortified border rather than tracing a marvellous continuum. Let’s think again. Lowery is an extraordinary poet, known to deliver aided by a ventilator, not using it as a prop but as a tetraplegic speaker’s necessity. His words speak potently, charged to carry them way beyond the page. Those poetic shapes in response to the images satisfy visually, but it’s far from this story’s end.

We all tell our influences. In a loose sense, in any and every medium, creative work cannot be entirely ekphrasis-free, but perhaps in the fractures and possibilities of these exchanges the real magic happens.

And this book is indeed magic.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply