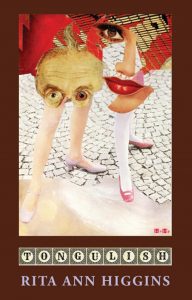

Tongulish

Rita Ann Higgins’s eleventh poetry collection, Tongulish, pulses with conversation. It is a stroll down the street; the ambience of the spoken word splayed across the page. Conversation is volatile and ever-changing from subject to subject; in much the same way, the poems within the collection cover a plethora of subject matter. It is a book of talking in all its diversity, from class divisions to mythology. Special regard for the Irish language makes the collection precisely what you might hear if you listened on a packed bus making its way through Higgins’s hometown of Galway.

Rita Ann Higgins’s eleventh poetry collection, Tongulish, pulses with conversation. It is a stroll down the street; the ambience of the spoken word splayed across the page. Conversation is volatile and ever-changing from subject to subject; in much the same way, the poems within the collection cover a plethora of subject matter. It is a book of talking in all its diversity, from class divisions to mythology. Special regard for the Irish language makes the collection precisely what you might hear if you listened on a packed bus making its way through Higgins’s hometown of Galway.

The first poem in the collection, “Easy on the Ankle”, implies this very notion of a bus ride with each stanza telling a different story, characterising how the ear alights from one subject to the next. The first stanza brims with conversation with little fragments hanging in line that seemingly make no sense to the listener, and a colloquial code passed between close friends:

he was Long-John-Silvered

without a spoon in his mouth.

He’d have ended up sucking

his porridge through a jackdaw.

Short lines, with full stops omitted, stir in the mind the speech and breath of a rapid talker, somewhat different from the nonchalant speaker a couple of stanzas later:

Anything babe, you can have anything,

even my maggot collection.

And you know the way I am

about them maggots.

Higgins gives the impression of a variety of different speakers on the page, attention flitting between them. Perhaps, the poem’s hidden magic is the layering of a deeper message beneath the pleasant gossip – a gesture recurrent throughout the collection. On this bus ride alone, we are witness to strife in the workplace; to violence and romantic disharmony. “Easy on the Ankle” holds a mirror to the rest of the collection: a perfect gathering of social issues harnessed by a smooth tongue.

Surprisingly, the title poem, “Tongulish”, does not appear first in the collection; but, rather, on page 32. Although, perhaps, initially puzzling in its placement, it acts as less the title-piece and more as a gentle reminder mid-conversation: “remember to pay attention to the language”, it seems to say when we finally come around to it. Where before we might have been on a bus in Mijas, contemplating “Getting Older”, or in a tent with the wife of “Caligula”, we are reminded to listen to the words on the page and enjoy them as much as their messages – sound acting as the gateway to the meaning. The poem is a microcosm of the greater collection, bursting with enough colloquialisms and onomatopoeia to fill the rest of the book:

Give me garbled, slurred, rasp,

a fricative on its own

or leaning on a noun.

I’ll take metaphor, babble,

weight-watcher verbs with no taste,

jejune compounds, or con words,

whisper, puggle, click or clack words.

A love poem to the art of speech, it seems to mount a rebellion of sound against “that aching silence / that never satisfies any gulf”. The collection as a whole carries this legacy by folding deeper messages within its conversation, such as “The Women of 1916”, a fast-paced dedication to the women of wartime Ireland. The format pulls the eye through the poem like an ear through a story and the reader finds themselves drawn in by the women and their tales.

The very name of Higgins’s collection, Tongulish, is enough to reveal exactly what lies within: a delightful cacophony of words both dictionary-bound and invented alike; a sense of language that could breach any divide and rumble along in the air of any bus. But, it is not an empty language of superficial matters: each word comes with its own weight and its own issues; each peculiar word with an important story to tell.

And oh…am I looking forward to hearing her at stAnza next week!