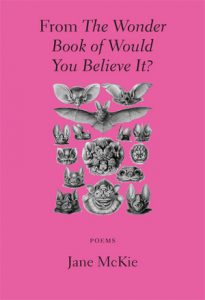

From The Wonder Book of Would You Believe It?

This is Jane McKie’s third collection of poetry. Her first, Morocco Rococo, was published by Cinnamon Press and won the Sundial/SAC Prize for Best First Book in 2007. She then published Garden of Bedsteads in 2011 with Mariscat Press. She is a member of the Shore Poets group and teaches Creative Writing at the University of Edinburgh.

This is Jane McKie’s third collection of poetry. Her first, Morocco Rococo, was published by Cinnamon Press and won the Sundial/SAC Prize for Best First Book in 2007. She then published Garden of Bedsteads in 2011 with Mariscat Press. She is a member of the Shore Poets group and teaches Creative Writing at the University of Edinburgh.

A collection of graceful, restrained poetry that often takes its inspiration from science and the natural world, everything within is pared down to absolute essentials.

The series of three short poems titled, “A City of Floating Houses”, with an epigraph on loneliness taken from Haruki Murakami’s Sputnik Sweetheart, investigates three species of jelly fish: Olindias Formosa, the Flower-Hat Jelly; Physalia Physalis, the Portuguese Man-O-War, and Aurelia Aurita, the Moon Jelly. In “Olindias Formosa”, the poet describes its multi-coloured form, as

the many locks curling around

her lustrous flower cap,casting her pink-beaded cornrows

out like so many arms.

In “Physalia Physalis”, the sense of danger associated with this creature is illuminated:

on the surface, a rain-mauve

sail, translucent corona.Underneath, tentacles like

inky, uncoiled colons.

In “Aurelia Aurita”, the jellyfish

balloon like giant shiitake

or polychromatic

x-rays of a cranium [.]

McKie conjures a sense of loneliness in the jelly fish’s untouchability and their drifting nature.

However, not all the poems in the collection address natural history. One piece especially, “A White City Underground ” deals with human imagination, myth and storytelling in a highly inventive way. The narrator’s young niece is telling her aunt about a fantastical place she has supposedly just returned from,

The white palisades, the walkway beside

the forgetful river where everything –

from broken spectacles to buckle shoes –

is lost. Well, I don’t buy a single word,

this supposed place of the dead, a mile

under earth….

Later, after the narrator has dropped her niece off at the bus stop, she pauses,

catch myself puzzled, just then recalling

how long it was after she disappeared

before her slender bones were even missed.

Casting the narrator’s niece into the role of Persephone, she reanimates ancient mythology into the present day.

Several of the poems in this collection feature bats. McKie asks us to consider what it is like to be a bat. In “Not like us”, she muses:

I can only guess – is it like nestling

in a nook of velvet with a welter

of siblings? One minute hunger, the next

a snap of jaws around a fizzing whit

of insect life that, to a human, might

taste of white peach or ice-cold Prosecco?

“Old Inhabitants of our Home” looks at bats very much from a human perspective. Here, the poet returns to a childhood visit to her grandmother’s caravan near a bridge where bats roost.

When we get in, she’ll scrub our smeary hands

with amber Pears before telling us off for rousting

the ‘old inhabitants’ – bats nested like knottedBrown pennants under the bridge….

But like all children, they forget her grandmotherly chiding and play under the bridge, laughing at their echoes:

… we forget the bats

until they drop, swoop and settle – blind

and fickle – almost, not quite, cuffing our heads.

The final bat poem again focusses on the bat’s experience of itself. In “Strange Ears and What they Hear”, McKie imagines what it must be like to have a bat’s super-sensitive hearing. She imagines that

they must ache for the void, pound

with violent need

to devour

the membranous tymbalsof tiger moth

forceps of earwig,to pick off noise

(and the echoes of noise) [.]

There is a philosophical sense of wonder in these bat poems that shows the poet’s deep engagement with nature.

Jane McKie’s new collection is not only technically accomplished; it draws the reader in to a different way of looking at the world.

Leave a Reply