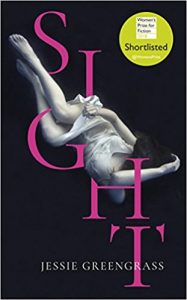

Sight (Shortlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction)

On the cover of Lia Purpura’s marvellous collection of lyric essays, On Looking, there is a close-up photograph of a strange bony object with clavicle-like hollows and spinal protuberances. Our classroom exchanges about exactly what this represents always lead to discussions on Purpura’s themes and poetics. Jessie Greengrass’s second book will spark exactly those kinds of exchanges for she stretches the novel as long form fiction. Written in the cadences and rhythms of memoirs, Sight makes forays into philosophy, essay and history writing, and then back again into fiction, inviting us to think about what she does, and also why and how.

On the cover of Lia Purpura’s marvellous collection of lyric essays, On Looking, there is a close-up photograph of a strange bony object with clavicle-like hollows and spinal protuberances. Our classroom exchanges about exactly what this represents always lead to discussions on Purpura’s themes and poetics. Jessie Greengrass’s second book will spark exactly those kinds of exchanges for she stretches the novel as long form fiction. Written in the cadences and rhythms of memoirs, Sight makes forays into philosophy, essay and history writing, and then back again into fiction, inviting us to think about what she does, and also why and how.

In many ways, the ‘whys’ and the ‘whats’ take care of themselves, and in doing so reveal the ‘hows.’ Sight is a meditation on motherhood (its corollary ̶ being a daughter ̶ and its extension, being a woman). The novel’s central spine follows an unnamed “I” who ponders her pregnancy, her constitutional ambivalence about motherhood ̶ the push and pull of obligations and resentments, heart-constricting fear, melancholic love and loss. This leads her back to reflect on her own mother’s illness and death, her psychoanalyst grandmother’s impact on both women, and the strange contexts of their lives. At once cerebral and then also visceral, understood through touch and feeling (or lack thereof), this twinning of the mind and the body occurs in lush syntax(es) and lyrical cadences, in complex and controlled sentences that thinks and writes the body philosophically, and with feeling:

in pregnancy’s third trimester, these sudden squalls of tears that burst from nowhere [is]… a further reminder of how little my body is within my control and there is nothing I can do but wait… for my body to complete the task it has been set, heedless of my intercession, and for the inevitable but unpredictable tract of pain beyond, for exhaustion and… the tumbling rush to interpret a newborn’s needs.

Woven into this narrative are other stories that echo the novel’s concerns at a slant, presented as the narrator’s historical research: Wilhelm Röntgen and a brief early history of the discovery of x-ray; psychoanalysis as a family romance; the history of anatomy told allusively through John and William Hunter’s preoccupations. These stories catch and repeat the inner-outer dynamic embedded in the novel’s insights into motherhood: how to see and read interiority (including your born and unborn child), and whether this “hidden made manifest” process is really a confrontation with mortality. Thus on perceiving her skeletal hand imprint on the x-ray plate, Bertha Röntgen, “who had not doubted those things that constituted her – her skin, her thoughts: the single object that was flesh housing mind,” remarks, “it is… like seeing my own death.”

Motherhood’s interchangeability is also an exploration of time and narrative: the backward glance into a childhood past; the forward trajectory of a daughter’s departure; moments of regression in adulthood as a “memory taught and retaught, the epigenetics of comfort.” When and where one occupies these positions of adult and child are to do with the forward progress of time and time frozen (repetition); the “ritual[s] of water and cloth” for a dying mother makes the past flare up suddenly:

I see the outline of my mother’s hands beneath the skin of mine… I hear her voice in mine performing the liturgy of endearments… and I wonder if these things are soothing in themselves or if… through generational repetition they have become that way, a memory taught and retaught…

Much like the interpretation of dreams, the past flows into the present and into an imagined future, and back out again; time is both subjective and also curiously impersonal. Much like Freud’s model of the unconscious, Sight is palimpsestic, relying on a disjunctive layering of stories, both in their differences and their similarities, to tell or to disguise the central story.

While not all the adjacent stories are equally weighted or charged (the first and last do not contain the frisson of Freud’s tale, and the lush discursive register sometimes ebbs a little into straight reportage), this is a novel one can’t help but admire. Major literary awards must beckon.

Leave a Reply