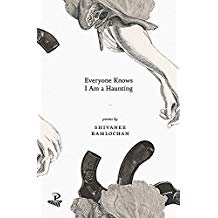

Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting (SHORTLISTED FOR 2018 FORWARD PRIZES FOR POETRY: THE FELIX DENNIS PRIZE FOR BEST FIRST COLLECTION)

Shivanee Ramlochan is a jack-of-all-trades. She is an arts reporter, book blogger, editor and reviewer for The Caribbean Review of Books, and a poet living in her native Trinidad.

Shivanee Ramlochan is a jack-of-all-trades. She is an arts reporter, book blogger, editor and reviewer for The Caribbean Review of Books, and a poet living in her native Trinidad.

Her first collection, Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting, opens with a poem entitled “A Nursery of Gods for My Half White Child”, introducing us to a state of conflict. The narrator and her family are stuck between worlds, symbolised by the various myths, religions and sexualities explored. The narrator struggles to tell her child what to believe in; Ganesh, Kali and Krishna are named but none of them seem quite right. However, in the last lines of the poem, we begin to see what she really believes in: the power of women, “shrieking, floating, bastarding into birth, / called to the world of the living between the harvest of your thighs”.

The difficulty of birth reminds us of the life-giving capabilities of the female body, making the women appear god-like themselves in turn. Menstruation, the mud and dirt of nature also evoke a sense of connection to creation that is marked as entirely female in the collection. However, Ramlochan is not only interested in gods, she is also intrigued by devils:

From this fabric, from the persistent earth, she will wrangle

greater things than men can fathom.

She will wrestle squalling tar infants from the mire, and those children

shall stumble upwards, slicing through the spines of men

who have offended their mothers.

Witches, demons, and abortionists live in these pages, all trying to find belonging in a world that fears them. Lilith, Adams first, and more importantly, defiant wife, occurs in a variety of guises throughout the book. A woman talks of her daughter who is trying to live a normal life whilst hiding her demonic nature:

Love,

I saw our daughter in the grocery store again.

This time, she’d discarded her old shoes,

because finally,

her hooves were coming through.Yet Lilith herself is not frightened:

Mother, don’t bother. I’m covered. I’ve got it

sorted […]

The language Ramlochan uses often melds the mythic with the modern, for example the use of vernacular expressions and creolised English, which display a defiant tone throughout the poems:

Play yuself.

Clay yuself.

Wine en pointe and wine to the four stations of the cross,

dutty angel[.]

There are monstrous women owning their heritages; women re-writing the creation myth to suit their own needs, entwining both Christian and Jewish faiths:

Don’t turn the lamps down.

(…)

In the first week, the vines, the shoots, the leaves helped us make soup.

Language is a form of creation and Ramlochan understands that history begins with words, with humans telling stories. She is also aware that her experience as a woman is not the only experience. She knows that even as a woman of colour, she is not the only person who faces injustice. She writes about the male experience of being gay, about fatherhood and police brutality. As the book continues, the mythical makes way for gritty realism in conversations about the immorality of the legal system. Experiences of reporting sexual assault are shown to us with honest and empathetic clarity:

Don’t say rapist.

Say engineer of aerosol deodorant because pepper spray is illegal,

anything is illegal.

Fight back too hard, and it’s illegal>your nails are illegal[.]

Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting is a tender exploration of familial love and culture as an open, honest question, and one that clearly appreciates the diversity of human experience, which Ramlochan undertakes through her play with language. She may be unsure, but she finds [ a measure] of self-belief:

This is how you survive it.

When the doctor stitching the torn seam of your sex

pauses to tend to a text message,

spit on him.

Leave a Reply