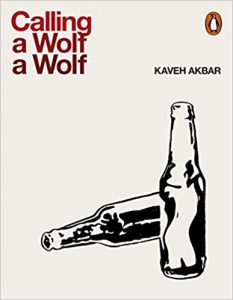

Calling a Wolf a Wolf (SHORTLISTED FOR 2018 FORWARD PRIZES FOR POETRY: THE FELIX DENNIS PRIZE FOR BEST FIRST COLLECTION)

Kaveh Akbar’s poetry is captivating not only for its beautiful turn of phrases but also for its more profound musings in evocative lines that linger: “eternity looms/ in the corner like a home invader saying don’t mind me I’m just here to watch you nap”. Yet Calling a Wolf a Wolf isn’t simply a sum of various poetic features executed well ‒ so well executed, and at times quite brilliantly so, that reading becomes quite literally a guilty pleasure. Akbar seems aware of how personal issues affect his art; he writes with rich metaphors and images, yet he also handles difficulties well. It would be easy for Akbar to offer a collection which consists merely of well-painted images but, instead, he gives a new perspective on the troubling issues at hand. Whether it is correct to enjoy this “from a dark place” work is a separate conversation to be had outwith this review.

Kaveh Akbar’s poetry is captivating not only for its beautiful turn of phrases but also for its more profound musings in evocative lines that linger: “eternity looms/ in the corner like a home invader saying don’t mind me I’m just here to watch you nap”. Yet Calling a Wolf a Wolf isn’t simply a sum of various poetic features executed well ‒ so well executed, and at times quite brilliantly so, that reading becomes quite literally a guilty pleasure. Akbar seems aware of how personal issues affect his art; he writes with rich metaphors and images, yet he also handles difficulties well. It would be easy for Akbar to offer a collection which consists merely of well-painted images but, instead, he gives a new perspective on the troubling issues at hand. Whether it is correct to enjoy this “from a dark place” work is a separate conversation to be had outwith this review.

An Iranian-American poet whose work has appeared in several major publications such as The New Yorker, The New York Times, Poetry Magazine and many more, Akbar’s latest collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, deals with his relationship with addiction, his grappling with faith and desire, and the issues that arise from those conflicts. Akbar’s poetry is written as personal as you would expect from a poet actually confronting the issues that he is. Needless to say, the poetry is dark and compelling.

The most notable quality of the verses is Akbar’s ability to create the most arresting images to convey how individual his experiences are. The themes in Calling a Wolf a Wolf are written using powerful and sometimes obscure images, which both enhance the poet’s sense of isolation whilst attempting to faithfully convey his experiences. Perhaps this is why some of Akbar’s phrases seem abstract and inaccessible. For example, “some moths don’t even have mouthparts using/ only stored caterpillar energy/ their lives are measured in days scissoring/ tributaries”. Yet, despite their obscurity, Akbar’s skillful lines grab the reader’s attention and stay with him/her. Images are potent and striking, and their weight and the issues they bear sits in your chest for a while. In “Portrait of the Alcoholic Three Weeks Sober”, I found these lines particularly captivating:

Imagine being the oil boiling away an entire person. Today, I’m finding problems in areas where I didn’t have areas before. I’m grateful to be trusted with any of it: the bluebrown ocean undrinkable as a glass of scorpions…

This collection is varied in form and structure but the most interesting of these are written without punctuation or uppercase lettering. There might be conventional stanza breaks, but the experimental style invites us not to be passive but to read actively, to interpreting his words. The reader must decide for themselves where to pause for breath and also what its effects might be:

the prophets are alive but unrecognizeable to us as calligraphy to a mouse for a time they dragged long oar strokes across the sky not they sit in graveyards drinking coffee forking soapy cottage cheese.

At times you can imagine these poems being read in one breath without pause, to convey the pouring of emotion; at other times the reader can play with cadences and stresses, thus choosing which lines to emphasise. This makes repeat readings different.

A complicated relationship arises between artist and audience when the work comes from a dark place. Th art can be very moving, engaging and is often amongst some of the artist’s best but its price can be the creator’s own physical, mental or emotional well-being. As a result, enjoyment of art that is born out pain and conflict, puts us in an uneasy moral place.

Leave a Reply