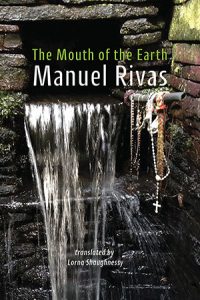

The Mouth of The Earth

Manuel Rivas,

(Translated by Lorna Shaughnessy),

(Shearsmans Books 2019); pbk, £9.95

Manuel Rivas’ latest collection of poetry The Mouth of The Earth touches on themes familiar to his previous fiction, poetry and journalism: nature, historical memory, invisibility and necessary attention.

Manuel Rivas’ latest collection of poetry The Mouth of The Earth touches on themes familiar to his previous fiction, poetry and journalism: nature, historical memory, invisibility and necessary attention.

In The Mouth of The Earth, it is the economic use of language that initially impresses. Witness the expanse of the three lines that open ‘The Curve’:

The worst wound

Is cut in a straight line.

Observe the great scar of the horizon.

Words are distilled with such precision and intention, it is like being invited to lean in and observe a droplet hit the water surface before stepping back in order to take in the expanding, concentric circles that are subsequently set in motion.

Lorna Shaughnessy’s remarkable translation from the original Galician to English deserves mention. The poems quietly insist on the importance of being alert to what is being said (by language, by what is left unspoken or unformed). If Rivas amplifies the voices of the dispossessed or overlooked, Shaughnessy also extends the reach of these voices to a new audience. Since the transition to a second language still renders the poetry with such startling accuracy, we can assume nothing has been lost in translation.

In the first section entitled ‘The Earth That Hides’ Rivas applies the quiet focus of a born naturalist to excavate dialogue between nature and humanity. Here the earth embodies wisdom that lies hidden ‘until the time comes to reveal itself’.

To say that Rivas places words carefully is an understatement. He knowingly holds off until the exact moment when a single word can be dropped, tilting the entire axis of the poem with devastating effect:

Because the wolf limped

Wilfully.

These poems are shot through with absence, substance fading by the time we reach the end of a line. In ‘Sabucedo’, we hear ‘a whinnying of horses not yet born’. In ‘The Blackbird’ we imagine the star unknown to the night.

The play between the material and the intangible aspects of human life become the focus of ‘Mother’s Mountain’ where the inheritance of a small piece of scrubland reveals something far greater in scope: a past enfolded within the present; the intangibility of borders (the lightning-split tree inspires the conclusion ‘So now I own some sky as well’); a hidden land indivisible from the poet himself.

In the second section, ‘The Ohio Scales’, the repeated image of weighing scales offsets the impossibility of capturing unquantifiable human experience illustrated by ‘a litre of thirst’ or a ‘kilo of hunger’.

‘The fixed stare of the weighing scales’ becomes slightly sinister when juxtaposed with the third and final group of poems, ‘Funeral Orations’. Here, remembrance is crucial as the author makes deliberate reference to each death in the annotated notes, bringing renewed attention to either forgotten injustice (as with the brutal murder of the gypsy basket weavers) or an act of heroism to be celebrated (as with the skipper who challenges the dumping of nuclear waste and affects change).

The titular poem `Mouth of the Earth’ is written from point of view of earth itself and centres on the mass graves resulting from the Spanish Civil War. The line ‘currency forged from forgetting’ reminds us that the earth does not forget, echoing the opening poems. ‘The earth swallowed them up’ but still the land ‘feels their hunger’.

Tellingly, the final section is prefaced by the epigraph, ‘A book sprouted from his dead body’, taken from the poem by Cesar Vallejo. As Vallejo himself once stated, the text is born out of life but does not simply return to nature with the death of its creator. Similarly, The Mouth of the Earth immortalises silence, absence and death. Rivas urges us to observe and listen closely as the poems give voice to the voiceless – the earth, the dead, the half-forms that defy measure, the past, injustice buried. In our contemporary climate of endangered nature, language and political truth, this is poetry of extraordinary significance.

Leave a Reply