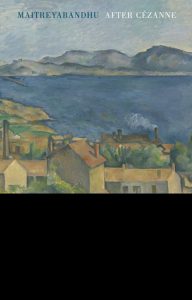

After Cezanne

This collection, Maitreyabandhu’s third with Bloodaxe, has an unusual format. It is illustrated with 25 paintings by the post-Impressionist painter, Paul Cezanne, and together the poems in the collection form a meditation on aspects of the artist and his work.

This collection, Maitreyabandhu’s third with Bloodaxe, has an unusual format. It is illustrated with 25 paintings by the post-Impressionist painter, Paul Cezanne, and together the poems in the collection form a meditation on aspects of the artist and his work.

Maitreyabandhu, who studied fine art at Goldsmiths, trained as a Buddhist monk and now lives in a Buddhist Community in London, where he teaches meditation. He has won several awards for his poetry, including the Keats-Shelley prize, the Basil Bunting Award and the Geoffrey Deamer Prize.

After Cezanne deals with the painter’s struggle to realise his revolutionary method of painting, that is to paint the act of seeing. It also charts his friendships with such luminaries as Zola, Rilke and Pissaro. A foreword by Christopher Lloyd (Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, 1988 – 2005), claims that ‘Cezanne had a profound knowledge of classical literature and of French authors. For many years he was on good terms with the novelist Emile Zola and if he had not chosen to be a painter he could have been a poet’. This sets the tone for a collection of poems that delves into the act of painting, the imagined feelings of Cezanne’s sitters and the composition of his still lives, with powerful effect.

In ‘The Apple’s Progress’, the poet focuses on the spatial relationships between the still life’s objects; it’s fruit, bottle, cups and saucers, against its background cloth and dresser. The act of looking here is almost forensic in its piercing observation:

This orange, if it is an orange, finding

its necessary weight. This lemon turned

towards the orange, which is so emphatically

full-face. This propped up apple almost erotic

in curvaceousness and stem-end. This distance –

intimate, standoffish – between the apple

and a second lemon. This fellowship of fruit,

these colours conversing and apart.

The artist’s wife, Hortense, was looked down on by Cezanne’s family and friends, as a vulgar, shallow woman, but she stayed with the artist for several years and bore him a son before they eventually married. She endured sitting for her portrait to be taken on many occasions over the years. Cezanne was notoriously harsh with his sitters, losing his temper if they moved even slightly.

Two poems deal with Rilke’s reactions to seeing paintings of Hortense at the Salon of 1907. Rilke wrote to his wife, Clara, and to the painter, Paula Modersohn-Becker, about the pictures and the poems ventriloquise his correspondence:

the colours of her face, how vulnerable

she seemed, and lost, then in another painting,

clutching a handkerchief or possibly a flower –

so slight she seemed to levitate.

He rhapsodised the colour of her dress,

The wallpaper and how, walking home in rain

along Rue Cassette, he was already forgetting

which blue was next to which and what

the sleeves had said, what the armchair meant.

Again, in a later poem in the collection, Rilke is invoked:

How awkward she seemed, the picture cut in half,

the light and darker side choreographed

by her cloudy blouse and strangely missing hands.

Count Kessler turned to me and said ‘Cezanne

pursues the line of beauty here – a line

that flowers, literally flowers, in the design

of the buttoned bodice meeting at the throat

in a petal-like white collar revealing an almost

stamen neck, columnar, to emphasise

the tilt of her wounded head and mismatched eyes’.

In these and other poems in this collection, Maitreyabandhu has an extraordinary depth of understanding of the paintings he observes. His compassion for Cezanne’s mission sings out in the poems. Maitreyabandhu has obviously immersed himself in the details of Cezanne’s life, as well as critical reaction to his work by contemporaries. There are illuminating notes on each of the poems at the end of the collection which illustrate the depth of the poet’s research into this important painter, who paved the way for Modernism.

Leave a Reply