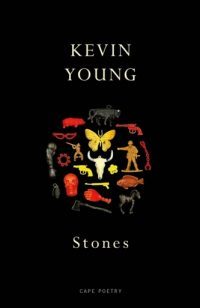

Stones (Shortlisted, TS Eliot Prize 2021)

Kevin Young’s accomplished collection of poems, Stones, moves with deliberate pace, an anodyne for those who have lost someone they will always love. The language is delicate and gentle—yet provocative in word and manner. In his review for The New York Times, David Orr describes Stones as a book about how families absorb and repurpose loss. Stones embraces grief by examining the root likeness of our ancestry—the way we grow into and out from our inheritance.

Composed of tercets, with rhymes and slant rhymes, the poems emphasise the inseparable connection between one’s heritage and identity; this relationship is made palpable through imagery. Young becomes a metaphorical horticulturist and uses poetry as an increment borer (instrument for measuring the rings on a tree). The collection concludes poignantly in ‘Balm’:

my dead have sown

Each year

they grow, gatherrings like trees

till I can’t count

no more.

Here, Young quantifies the time-hallowed nature of ancestry with pastoral imagery.

Our ancestors become part of our skeletal frame – the stem from which we soak up materials for life. They protect us, the way bark shields the cambium from outside weathers. The memory of their resilience – how they sang though ‘choked by ivy’ – grounds us in hope. Our ancestors are what water is to leaves on a tree; without them, we cannot be. Like helicopter seeds whorled away from the body of a great oak, we will grow to join the forest of our forefathers. ‘High Water’ makes visceral the tension and historical strain between different familial generations; though history often

Enters where

it is not

welcome [;]one’s heritage

… apologizes

& blesses

& barely says sorry –in a word

you could

call it family.

Stones is a spiritual collection. In ‘Kith,’ intergenerational members of an expanding family move ghostlike

among the blue

bottles – both the flies

& the glass[.]

The memory of them imbues significance on mundane objects. Young uses an Old English word ‘kith’ to build relationship with the past and the present. Toward the middle of the collection, in a poem of the same title, he writes:

Kith is what you find

in the cemetery, names

effaced from their graves,names you may not

know, but share

or share though don’t yet know[.]

To Young, the word kith represents both the living and the dead. ‘Kith’ describes them as

… outliving

the dead, but means

the dead too, resting

here on the sill[.]

Stones balances the temporal with the afterlife, building a middleworld where time is irrelevant. Here, memories overlay the collection’s present tense with phantoms from the past. The following poems depict ordinary scenes—a grandmother’s 85th birthday, childhood memories, thunderstorms, collecting fireflies—but these are softly burdened by an ‘evensong,’ a landscape where ancestors move and make music in the dark.

In ‘Mason Jar,’ the poet watches children capture fireflies and remembers his youth. This reminiscing moment suggests the cyclicality of life, a theme that is made visible in smaller illustrations, too, for example, the season’s change on tree or, when daytime turns to dreams. Towards the denouement, Young compares the presence of his ancestors to the ‘waning light’ of fireflies; how they drown

without the air

they are

meant for.

In ‘Evensong,’ Young’s ancestors are ‘little keeps’

yanked from the deep

after a long struggle –begging to breathe.

The memory of each one comes to life and is renewed when the

hat

wilts, heldover your heart to honor

today the dead[.]

(‘Mason Jar’)

In ‘Dog Star,’ Young writes:

Yet the wind won’t

go away

so easily, the stars remain& do not grey[.]

A boy—Young, or another—looks

up into them thinks

he’s seeing them first

tonight[.]

Young’s dexterity on one’s lineage and legacy melds both concepts into coherent stanzas of pastoral imagery where one’s ancestry, having glittered before, is now, in retrospect, so much more.

Shanley McConnell

Leave a Reply