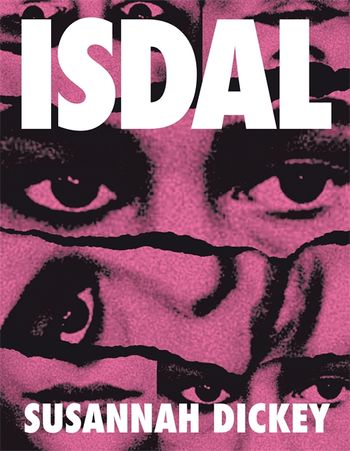

ISDAL (FELIX DENNIS PRIZE FOR BEST FIRST COLLECTION, FORWARD PRIZE 2023, SHORTLISTED)

Susannah Dickey

(Picador Poetry, 2023); pbk. £10.99

With two novels, four poetry pamphlets and an Eric Gregory Award already under her belt, the stunning quality of Susannah Dickey’s debut poetry collection should come as no surprise. ISDAL starts as a scalpel-sharp critique of the true crime genre and ends unravelling tangled notions of grief, empathy, exploitation and our near-pathological need to narrativize death (and life).

The collection is divided into three parts: ‘podcast’; ‘narrative’ and ‘composite’. Part one is a collection of poems telling the story of an investigation by two podcasters into the mystery of the Isdal Woman.

For the uninitiated, Dickey includes a succinct explanation of the Isdal Woman:

In November, 1970, a woman’s body was found at Isdalen in Bergen, Norway. Her status has been ‘Unidentified’ for _ years, _ months, _ days. She was severely burnt on the front of her body…but not the back…she died of a combination of carbon monoxide poisoning…and a barbiturate overdose. She has come to be known as the Isdal Woman.

It is key to note that this explanation comes before the table of contents. Its blunt tone stands in stark contrast to the sensationalist writing in part one. The poem ‘More Importantly!’, introducing both the hosts and their exploitative mission, is a prime example:

Two podcast hosts captain the story’s bounce and narrative thrust!

He’s English! She’s Norwegian! They need listeners to bestow their trust

and invest in this ten-part audio description of cruelty.

If ratings drop there’s been a failure of either execution or loyalty.

With its snappy exclamations, bouncing rhythm and playful rhymes, the poem allows us to imagine the hosts’ witty banter, incongruous with podcast’s morbid subject matter.

Another example of this mirroring is in ‘*Take this time to reflect on what we’ve described’. Dickey highlights the artificiality of True Crime podcasts with increasingly absurd examples of foley, all the while playing with sound herself intent makes little difference to sound fraying rope rubbed between hands is

good for sinister in the absence of rope use hair in the absence of hair use air…

In part two, ‘Narrative’, Dickey moves from poetry to essay. Her critique of the True Crime genre becomes more direct. Gone is the palatable playfulness of part one, replaced with frank reflection and violent imagery. Dickey posits the thesis that True Crime is a manifestation of our need to flatten death into a digestible story:

However, is True Crime actually concerned with empathy? I wonder if[…]this genre might not be more akin to stringing a sheep by its hindquarters and slitting its throat: an attempt to get closer to death without getting too close; an attempt to nuzzle against the notion of continuity, without the terrifying, onerous chore of dying.

The anonymity of the Isdal Woman makes her a prime candidate for this consumptive process:

True crime does not encourage grief, it encourages fetishistic interest, it cultivates our fascination with death, while also enabling an obsession devoid of empathy. As a single, deviant, unnameable woman, Isdal treads the line between ‘like us’ and ‘unlike us’ perfectly…Isdal is easily denied grief – she is not quite real. Her death, however, is just real enough.

Part three, ‘Composite’, returns to poetry. Isdal was found by a young girl out walking with her father and sister, and Dickey imagines her grown. Shielding her sister from the sight of the corpse, this (also anonymous), empathetic woman is the antidote to True Crime’s voyeurism. Gradually the lines between this figure and Dickey’s persona blur in the sharing of trauma, but ultimately Dickey rejects claiming this woman’s life to fashion a story out of:

All of this is ultimately speculative. I hope most of it is wrong.

[…]

There is no homogeneity of response to pain[.]

With such topical, biting satire and incisive critique, ISDAL is an exceptional debut. What elevates it, however, is the profound empathy at its core.

Kai Durkin

Leave a Reply