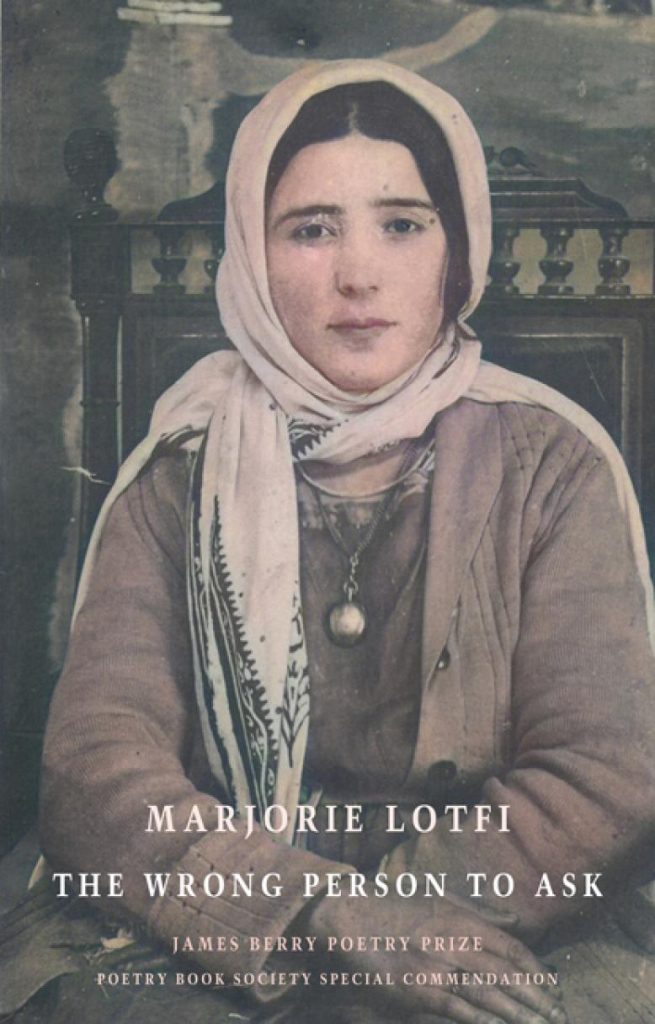

The Wrong Person to Ask (Awarded, Forward Poetry Prize for Best First Collection)

Marjorie Lotfi

(Bloodaxe Books, 2023); pbk, £10.99

Majorie Lotfi was born in the United States and moved to Tehran as a child, and then back to her American mother’s hometown of Ohio on the cusp of the Iran Revolution. Currently living in Edinburgh, she seems to have moved around a fair bit. This debut title comes to terms with displacement and settlement—the tug of the past, linguistic heritages, absence and presence, unbelonging and alienation as much as hospitality and reciprocity between strangers—using the contours of Lotfi and her family’s journeys to put together a collection that is full of heart even as it tackles tough political themes.

Divided into two, the first section of The Wrong Person to Ask’s diptych seems stronger and more tightly woven together—perhaps because its assemblage of poems sees them respond to each other and develop more organically (or so it seems even though they were published in different magazines and anthologies, and times). What you leave as you move away from ‘home’ is visceral—a gut punch—almost as if pieces of your body have been left behind. ‘Refuge’ is just that, taking its inspiration from Frances Bruno Catalano’s sculptural figures with missing bodily parts and sections,

Take out

his thighs, but leave

his knees to buckle

at kindness, and the lack

of it.

There is a twist in the last lines of the poem, however, for it ends with a reminder of what we do to others when forget they are also human:

Instead, nail

his feet to the planks

of the pier and let him try

to take another step.

Two poems respond to ‘the signing of and then withdrawal of the Iran Nuclear Deal’ at a slant, and is more powerful for it. Here Lotfi’s own call and response—‘ask’ and ‘say’—are done not at the level of grand political deals or impersonal ideologies, but of individual lives… and this really is the strength of the collection as a whole. In these two poems, remembering small domestic celebrations and rituals such as the making of baklava or the drinking of tea, remembering a cousin without employment despite his training and education, recalling the homely spaces of houses lived in in Iran—such memories are full of heart. The effects of alienation and displacement here are not generalised but felt by singular individuals and families:

Ask about Ameh, her arms around my skinny frame,

or how I can have forgotten Farsi and the sound

of her voice bidding me each night to let the day go.

Melancholic, reflective tones and also intimacies pervade this first section, reminding us that politics is as much about people as more abstract stuff like nations or border security. In ‘Two Grandmothers’ and ‘Maman Bozorg’, hospitality and reciprocity between one individual and another across the cultural divide can arise if we but strip away much of the ideological baggage we carry around. In ‘Riding the Line’ the regime’s guards also remember how it feels like to ride on skateboard like the teenagers they see out and about. Yet dangers are not forgotten, threats not ignored—‘Riding the line’ is printed facing the poem, ‘The gun in its holster’, and while the former poem’s teenage boys manage to return to supper, it ends with the line ‘nothing broken, nothing said’. Some poems respond to documentary pictures of children on boats, or photographs of young children in Gaza, turning poetry into a humane form of lyric witnessing. And Lotfi is particularly good at holding contraries in the same gesture, letting readers feel their full force as they decide how to read. ‘Picture of Boy, Looking Away’ is not only of the twelve year old Abdulrahman atop the rubble that was his home, but is also about us looking at that picture, wanting to turn it into a form of trauma porn over which we can express pity.

Section two of The Wrong Person to Ask sustains some of the themes and notes—belonging and loss—of the first section but the landscape is more distinctly Scottish, with poems featuring coastal beaches, fishermen and sailors journeying, a lighthouse keeper, and more. The beauty of the sea, as well as its darkness, is threaded through with images of shelter and light (from the lighthouse, from a candle at the window, from a vigil). If some of those emotional resonances from the section seem more diffused here, there are beautiful poems too of home and unhomeliness; the metaphor of the sea, its horizons, dangers as well as its mutability carry some of the force of section one even if it is presented at one remove. The Wrong Person to Ask begins with the most beautiful epigraph from John Burnside to suggest that poetry is a form of a prayer, a soulful gift. This collection is written simply, with great clarity, and few fancy embellishments and tricks; but sometimes simplicity is the hardest thing do to. Lotfi is most certainly not the wrong person to ask.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply