[…] (Shortlisted, Forward Poetry Prize Best Collection)

Fady Joudah,

(Out-Spoken Press, 2024); pbk £11.99

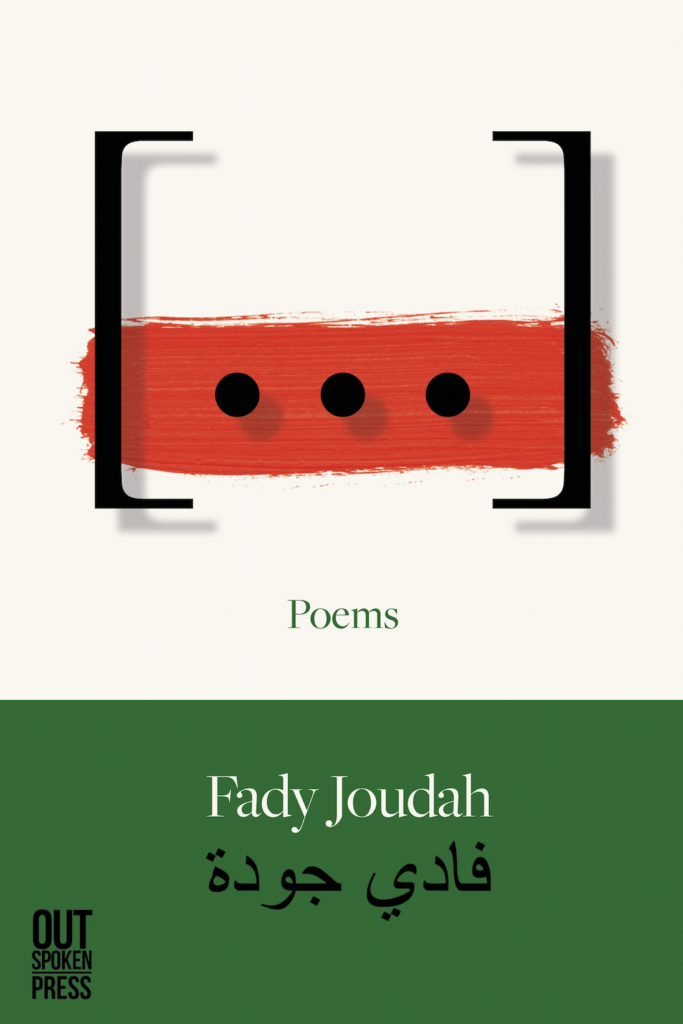

Shortlisted for the 2024 Forward Prize for Best Collection, Fady Joudah’s seventh poetry collection […] articulates, paradoxically, the silenced and unspeakable. Comprised predominantly of poems similarly titled ‘[…]’, navigated by a narrator who identifies as ‘unfinished business,’ this collection deconstructs political boundaries from the margins, giving voice to intergenerational Palestinian experiences amidst a wider lack of empathy and understanding. The red, green, white, and black colour palate of the front cover draws attention immediately to the Palestinian identity of Joudah’s poetic narrator. Significantly, the title […] is stamped in formal typography over what appears to be a red smear of blood, a symbolic attempt to cover up violence and bloodshed with a bureaucratic silence. Simple yet effective, the paratext establishes political context and Joudah’s intricate practice, communicating violent experiences that are often ignored or suppressed.

The pictographic title is indeed ironic given Joudah’s ability to challenge attitudes towards the ongoing war in Gaza unflinchingly, especially those promoted by the widespread presence of Internet-facilitated protests:

If the spirit says scream, I scream,

you scream, we all scream

for or against genocide on livestream[.]

Skilful interweaving of repetition, rhythm, and rhyme provides reminiscences of the ‘we all scream for ice cream’ chants from childhood, playing on infantile turns of phrase to expose immaturity and naivety in the face of conflict, and deftly navigating tensions between innocence, ignorance, and violence. Amidst an ‘old war’ that is ‘eligible for renewal online’, the narrator confronts the consciences of a predominantly Western media gaze, starkly reminding readers that ‘whoever gets to write it most / gets to erase it best.’ He refuses to allow his suffering to be rewritten or commodified into a cure for their guilt by articulating that:

like a poppy I am shattered

into your nostrils or milled

within the hard exoskeleton

of a pill the nation

prescribes to you for my pain.

Medical imagery and themes of healing arise consistently, which is unsurprising given Joudah’s physician background. Admittedly, ‘not everyone / is a physician // but sooner or later everyone / fails to heal,’ is exposed through poetic engagements with those directly affected by the war:

clearing the man-made rubble

with their bare hands,

disfigured by dust

into ghosts[.]

Dismantling the distance created through the detached consumerism of media coverage, […] articulates consequences of war in a way that is impressively lyrical without becoming romanticised; a war lyric that flouts more conventional forms and utilises the vividness of poetic craft without censoring or overly embellishing brutal realities of this conflict. Joudah’s focus on absence, rather than describing what is visually present, exposes the tragic loss created through a universal sense of complicity: ‘suddenly you / can’t find my body, / can’t bury / what you can’t find.’

However, this investigation of conflict refrains from lingering too long on the assignation of accountability; rather than simply repeating this tone of anger throughout the whole collection, Joudah’s narrator counterbalances the collection’s often bleak settings with hope:

In Gaza, a girl and her brother

rescued their fish

from the rubble of airstrikes. A miracle

its tiny bowl

didn’t shatter[.]

The narrator ‘write[s] for the future // because my present is demolished’, a present that desires to be reclaimed as a ‘legible past’. This is especially apparent in the sequence poem ‘I Seem As If I Am: Ten Maqams,’ one of the few poems not titled ‘[…]’, which engages intertextually with classical Arabic poetry to explore a Palestinian experience that transcends time and moves beyond current geopolitical contexts. The reclamation of ancestry and identity ensures potential for hope and renewal:

In Arabic, pain is an anagram of hope.

In Arabic, dream is clemency’s twin.

In Arabic, Joseph holds lovelike a jug of wine.

And everyone’s forgiven.

Current political contexts are a crucial element of this collection, but they do not overshadow the expansive, spiritual, and hopeful aspects of the narrator’s Palestinian identity. A sensitively balanced collection that still communicates clear convictions, […] is highly topical and relevant reading.

Orla Davey

Leave a Reply